Manchester (/ˈmæntʃɪstə(r), -tʃɛs-/ ⓘ)[6][7] is a city and metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England, which had an estimated population of 568,996 in 2022.[4] Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92 million,[8] and the largest in Northern England. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The city borders the boroughs of Trafford, Stockport, Tameside, Oldham, Rochdale, Bury and Salford.

The history of Manchester began with the civilian settlement associated with the Roman fort (castra) of Mamucium or Mancunium, established c. AD 79 on a sandstone bluff near the confluence of the rivers Medlock and Irwell. Throughout the Middle Ages, Manchester remained a manorial township but began to expand “at an astonishing rate” around the turn of the 19th century. Manchester’s unplanned urbanisation was brought on by a boom in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution[9] and resulted in it becoming the world’s first industrialised city.[10] Historically part of Lancashire, areas of Cheshire south of the River Mersey were incorporated into Manchester in the 20th century, including Wythenshawe in 1931. Manchester achieved city status in 1853. The Manchester Ship Canal opened in 1894, creating the Port of Manchester and linking the city to the Irish Sea, 36 miles (58 km) to the west. The city’s fortune declined after the Second World War, owing to deindustrialisation, and the IRA bombing in 1996 led to extensive investment and regeneration.[11] Following considerable redevelopment, Manchester was the host city for the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

The city is notable for its architecture, culture, musical exports, media links, scientific and engineering output, social impact, sports clubs and transport connections. Manchester Liverpool Road railway station is the world’s oldest surviving inter-city passenger railway station.[12] At the University of Manchester, Ernest Rutherford first split the atom in 1917; Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn and Geoff Tootill developed the world’s first stored-program computer in 1948; and Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov first isolated graphene in 2004.

Manchester is contiguous with the neighbouring city of Salford, separated from it by the River Irwell. The M60 motorway, also known as the Manchester Outer Ring Road, runs around the city and joins the M62 to the north-east and the M602 to the west, as well as the East Lancashire Road and A6.

Toponymy

The name Manchester originates from the Latin name Mamucium or its variant Mancunio and the citizens are still referred to as Mancunians (/mænˈkjuːniən/). These names are generally thought to represent a Latinisation of an original Brittonic name. The generally accepted etymology of this name is that it comes from Brittonic *mamm- (‘breast‘, in reference to a ‘breast-like hill‘).[13][14] However, more recent work suggests that it could come from *mamma (‘mother’, in reference to a local river goddess). Both usages are preserved in Insular Celtic languages, such as mam meaning ‘breast’ in Irish and ‘mother’ in Welsh.[15] The suffix -chester is from Old English ceaster (‘Roman fortification’, itself a loanword from Latin castra, ‘fort; fortified town’).[14][13]

The city is widely known as ‘the capital of the North’.[16][17][18][19]

History

Main article: History of Manchester

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Manchester history.

Early history

Main article: Mamucium

The Brigantes were the major Celtic tribe in what is now known as Northern England; they had a stronghold in the locality at a sandstone outcrop on which Manchester Cathedral now stands, opposite the bank of the River Irwell.[20] Their territory extended across the fertile lowland of what is now Salford and Stretford. Following the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century, General Agricola ordered the construction of a fort named Mamucium in the year 79 to ensure that Roman interests in Deva Victrix (Chester) and Eboracum (York) were protected from the Brigantes.[20] Central Manchester has been permanently settled since this time.[21] A stabilised fragment of foundations of the final version of the Roman fort is visible in Castlefield. The Roman habitation of Manchester probably ended around the 3rd century; its civilian settlement appears to have been abandoned by the mid-3rd century, although the fort may have supported a small garrison until the late 3rd or early 4th century.[22] After the Roman withdrawal and Saxon conquest, the focus of settlement shifted to the confluence of the Irwell and Irk sometime before the arrival of the Normans after 1066.[23] Much of the wider area was laid waste in the subsequent Harrying of the North.[24][25]

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Manchester is recorded as within the hundred of Salford and held as tenant in chief by a Norman named Roger of Poitou,[26] later being held by the family of Grelley, lord of the manor and residents of Manchester Castle until 1215 before a Manor House was built.[27] By 1421 Thomas de la Warre founded and constructed a collegiate church for the parish, now Manchester Cathedral; the domestic premises of the college house Chetham’s School of Music and Chetham’s Library.[23][28] The library, which opened in 1653 and is still open to the public, is the oldest free public reference library in the United Kingdom.[29]

Manchester is mentioned as having a market in 1282.[30] Around the 14th century, Manchester received an influx of Flemish weavers, sometimes credited as the foundation of the region’s textile industry.[31] Manchester became an important centre for the manufacture and trade of woollens and linen, and by about 1540, had expanded to become, in John Leland‘s words, “The fairest, best builded, quickest, and most populous town of all Lancashire”.[23] The cathedral and Chetham’s buildings are the only significant survivors of Leland’s Manchester.[24]

During the English Civil War Manchester strongly favoured the Parliamentary interest. Although not long-lasting, Cromwell granted it the right to elect its own MP. Charles Worsley, who sat for the city for only a year, was later appointed Major General for Lancashire, Cheshire and Staffordshire during the Rule of the Major Generals. He was a diligent puritan, turning out ale houses and banning the celebration of Christmas; he died in 1656.[32]

Significant quantities of cotton began to be used after about 1600, firstly in linen and cotton fustians, but by around 1750 pure cotton fabrics were being produced and cotton had overtaken wool in importance.[23] The Irwell and Mersey were made navigable by 1736, opening a route from Manchester to the sea docks on the Mersey. The Bridgewater Canal, Britain’s first wholly artificial waterway, was opened in 1761, bringing coal from mines at Worsley to central Manchester. The canal was extended to the Mersey at Runcorn by 1776. The combination of competition and improved efficiency halved the cost of coal and halved the transport cost of raw cotton.[23][28] Manchester became the dominant marketplace for textiles produced in the surrounding towns.[23] A commodities exchange, opened in 1729,[24] and numerous large warehouses, aided commerce. In 1780, Richard Arkwright began construction of Manchester’s first cotton mill.[24][28] In the early 1800s, John Dalton formulated his atomic theory in Manchester.

Industrial Revolution

Manchester was one of the centres of textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution. The great majority of cotton spinning took place in the towns of south Lancashire and north Cheshire, and Manchester was for a time the most productive centre of cotton processing.[33]

Manchester became known as the world’s largest marketplace for cotton goods[23][34] and was dubbed “Cottonopolis” and “Warehouse City” during the Victorian era.[33] In Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, the term “manchester” is still used for household linen: sheets, pillow cases, towels, etc.[35] The industrial revolution brought about huge change in Manchester and was key to the increase in Manchester’s population.

Manchester began expanding “at an astonishing rate” around the turn of the 19th century as people flocked to the city for work from Scotland, Wales, Ireland and other areas of England as part of a process of unplanned urbanisation brought on by the Industrial Revolution.[36][37][38] It developed a wide range of industries, so that by 1835 “Manchester was without challenge the first and greatest industrial city in the world”.[34] Engineering firms initially made machines for the cotton trade, but diversified into general manufacture. Similarly, the chemical industry started by producing bleaches and dyes, but expanded into other areas. Commerce was supported by financial service industries such as banking and insurance.

View from Kersal Moor towards Manchester by Sebastian Pether, c. 1820, then still a rural landscape. Note the River Irwell in both paintings.

Manchester from Kersal Moor, by William Wyld in 1857, a view now dominated by chimney stacks as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution

Trade, and feeding the growing population, required a large transport and distribution infrastructure: the canal system was extended, and Manchester became one end of the world’s first intercity passenger railway—the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Competition between the various forms of transport kept costs down.[23] In 1878 the GPO (the forerunner of British Telecom) provided its first telephones to a firm in Manchester.[39]

The Manchester Ship Canal was built between 1888 and 1894, in some sections by canalisation of the Rivers Irwell and Mersey, running 36 miles (58 km)[40] from Salford to Eastham Locks on the tidal Mersey. This enabled oceangoing ships to sail right into the Port of Manchester. On the canal’s banks, just outside the borough, the world’s first industrial estate was created at Trafford Park.[23] Large quantities of machinery, including cotton processing plant, were exported around the world.

A centre of capitalism, Manchester was once the scene of bread and labour riots, as well as calls for greater political recognition by the city’s working and non-titled classes. One such gathering ended with the Peterloo massacre of 16 August 1819. The economic school of Manchester Capitalism developed there, and Manchester was the centre of the Anti-Corn Law League from 1838 onward.[41]

Manchester has a notable place in the history of Marxism and left-wing politics; being the subject of Friedrich Engels‘ work The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844; Engels spent much of his life in and around Manchester,[42] and when Karl Marx visited Manchester, they met at Chetham’s Library. The economics books Marx was reading at the time can be seen in the library, as can the window seat where Marx and Engels would meet.[29] The first Trades Union Congress was held in Manchester (at the Mechanics’ Institute, David Street), from 2 to 6 June 1868. Manchester was an important cradle of the Labour Party and the Suffragette Movement.[43]

At that time, it seemed a place in which anything could happen—new industrial processes, new ways of thinking (the Manchester School, promoting free trade and laissez-faire), new classes or groups in society, new religious sects, and new forms of labour organisation. It attracted educated visitors from all parts of Britain and Europe. A saying capturing this sense of innovation survives today: “What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow.”[44] Manchester’s golden age was perhaps the last quarter of the 19th century. Many of the great public buildings (including Manchester Town Hall) date from then. The city’s cosmopolitan atmosphere contributed to a vibrant culture, which included the Hallé Orchestra. In 1889, when county councils were created in England, the municipal borough became a county borough with even greater autonomy.[45]

Although the Industrial Revolution brought wealth to the city, it also brought poverty and squalor to a large part of the population. Historian Simon Schama noted that “Manchester was the very best and the very worst taken to terrifying extremes, a new kind of city in the world; the chimneys of industrial suburbs greeting you with columns of smoke”. An American visitor taken to Manchester’s blackspots saw “wretched, defrauded, oppressed, crushed human nature, lying and bleeding fragments”.[46]

The number of cotton mills in Manchester itself reached a peak of 108 in 1853.[33] Thereafter the number began to decline and Manchester was surpassed as the largest centre of cotton spinning by Bolton in the 1850s and Oldham in the 1860s.[33] However, this period of decline coincided with the rise of the city as the financial centre of the region.[33] Manchester continued to process cotton, and in 1913, 65% of the world’s cotton was processed in the area.[23] The First World War interrupted access to the export markets. Cotton processing in other parts of the world increased, often on machines produced in Manchester. Manchester suffered greatly from the Great Depression and the underlying structural changes that began to supplant the old industries, including textile manufacture.

Blitz

Main article: Manchester Blitz

Like most of the UK, the Manchester area was mobilised extensively during the Second World War. For example, casting and machining expertise at Beyer, Peacock & Company‘s locomotive works in Gorton was switched to bomb making; Dunlop’s rubber works in Chorlton-on-Medlock made barrage balloons; and just outside the city in Trafford Park, engineers Metropolitan-Vickers made Avro Manchester and Avro Lancaster bombers and Ford built the Rolls-Royce Merlin engines to power them. Manchester was thus the target of bombing by the Luftwaffe, and by late 1940 air raids were taking place against non-military targets. The biggest took place during the Christmas Blitz on the nights of 22/23 and 24 December 1940, when an estimated 474 tonnes (467 long tons) of high explosives plus over 37,000 incendiary bombs were dropped. A large part of the historic city centre was destroyed, including 165 warehouses, 200 business premises, and 150 offices. 376 were killed and 30,000 houses were damaged.[47] Manchester Cathedral, Royal Exchange and Free Trade Hall were among the buildings seriously damaged; restoration of the cathedral took 20 years.[48] In total, 589 civilians were recorded to have died as result of enemy action within the Manchester County Borough.[49]

Post–Second World War

Cotton processing and trading continued to decline in peacetime, and the exchange closed in 1968.[23] By 1963 the port of Manchester was the UK’s third largest,[50] and employed over 3,000 men, but the canal was unable to handle the increasingly large container ships. Traffic declined, and the port closed in 1982.[51] Heavy industry suffered a downturn from the 1960s and was greatly reduced under the economic policies followed by Margaret Thatcher‘s government after 1979. Manchester lost 150,000 jobs in manufacturing between 1961 and 1983.[23]

Regeneration began in the late 1980s, with initiatives such as the Metrolink, the Bridgewater Concert Hall, the Manchester Arena, and (in Salford) the rebranding of the port as Salford Quays. Two bids to host the Olympic Games were part of a process to raise the international profile of the city.[53]

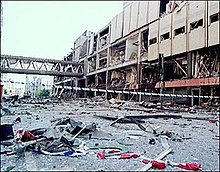

Manchester has a history of attacks attributed to Irish Republicans, including the Manchester Martyrs of 1867, arson in 1920, a series of explosions in 1939, and two bombs in 1992. On Saturday 15 June 1996, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out the 1996 Manchester bombing, the detonation of a large bomb next to a department store in the city centre. The largest to be detonated on British soil, the bomb injured over 200 people, heavily damaged nearby buildings, and broke windows 1⁄2 mile (800 m) away. The cost of the immediate damage was initially estimated at £50 million, but this was quickly revised upwards.[54] The final insurance payout was over £400 million; many affected businesses never recovered from the loss of trade.[55]

Since 2000

Spurred by the investment after the 1996 bombing and aided by the XVII Commonwealth Games, the city centre has undergone extensive regeneration.[53] New and renovated complexes such as The Printworks and Corn Exchange have become popular shopping, eating and entertainment areas. Manchester Arndale is the UK’s largest city-centre shopping centre.[56]

Large city sections from the 1960s have been demolished, re-developed or modernised with the use of glass and steel. Old mills have been converted into apartments. Hulme has undergone extensive regeneration, with million-pound loft-house apartments being developed. The 47-storey, 554-foot (169 m) Beetham Tower was the tallest UK building outside of London and the highest residential accommodation in Europe when completed in 2006. It was surpassed in 2018 by the 659-foot (201 m) South Tower of the Deansgate Square project, also in Manchester.[57] In January 2007, the independent Casino Advisory Panel licensed Manchester to build the UK’s only supercasino,[58] but plans were abandoned in February 2008.[59]

On 22 May 2017, an Islamist terrorist carried out a bombing at an Ariana Grande concert in the Manchester Arena; the bomb killed 23, including the attacker, and injured over 800.[60] It was the deadliest terrorist attack and first suicide bombing in Britain since the 7 July 2005 London bombings. It caused worldwide condemnation and changed the UK’s threat level to “critical” for the first time since 2007.[61]

Birmingham has historically been considered to be England or the UK’s second city, but in the 21st century claims to this unofficial title have also been made for Manchester.[62][63][64]

Government

Main articles: Politics in Manchester and Manchester City Council

See also: Manchester local elections, List of Lord Mayors of Manchester, and Healthcare in Greater Manchester

The City of Manchester is governed by the Manchester City Council. The Greater Manchester Combined Authority, with a directly elected mayor, has responsibilities for economic strategy and transport, amongst other areas, on a Greater Manchester-wide basis. Manchester has been a member of the English Core Cities Group since its inception in 1995.[65]

The town of Manchester was granted a charter by Thomas Grelley in 1301 but lost its borough status in a court case of 1359. Until the 19th century local government was largely in the hands of manorial courts, the last of which was dissolved in 1846.[45]

From a very early time, the township of Manchester lay within the historic or ceremonial county boundaries of Lancashire.[45] Pevsner wrote “That [neighbouring] Stretford and Salford are not administratively one with Manchester is one of the most curious anomalies of England”.[31] A stroke of a baron’s pen is said to have divorced Manchester and Salford, though it was not Salford that became separated from Manchester, it was Manchester, with its humbler line of lords, that was separated from Salford.[66] It was this separation that resulted in Salford becoming the judicial seat of Salfordshire, which included the ancient parish of Manchester. Manchester later formed its own Poor Law Union using the name “Manchester”.[45] In 1792, Commissioners – usually known as “Police Commissioners” – were established for the social improvement of Manchester. Manchester regained its borough status in 1838 and comprised the townships of Beswick, Cheetham Hill, Chorlton upon Medlock and Hulme.[45] By 1846, with increasing population and greater industrialisation, the Borough Council had taken over the powers of the “Police Commissioners”. In 1853, Manchester was granted city status.[45]

In 1885, Bradford, Harpurhey, Rusholme and parts of Moss Side and Withington townships became part of the City of Manchester. In 1889, the city became a county borough, as did many larger Lancashire towns, and therefore not governed by Lancashire County Council.[45] Between 1890 and 1933, more areas were added to the city, which had been administered by Lancashire County Council, including former villages such as Burnage, Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Didsbury, Fallowfield, Levenshulme, Longsight, and Withington. In 1931, the Cheshire civil parishes of Baguley, Northenden and Northen Etchells from the south of the River Mersey were added.[45] In 1974, by way of the Local Government Act 1972, the City of Manchester became a metropolitan district of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[45] That year, Ringway, the village where the Manchester Airport is located, was added to the city.

In November 2014, it was announced that Greater Manchester would receive a new directly elected mayor. The mayor would have fiscal control over health, transport, housing and police in the area.[67] Andy Burnham was elected as the first mayor of Greater Manchester in 2017.

Geography

See also: Geography of Greater Manchester

| Manchester |

|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) |

| JFMAMJJASOND7272518261103541355716866191164211377201272181093147821048172█ Average max. and min. temperatures in °C█ Precipitation totals in mmSource: Climate-Charts.com |

| showImperial conversion |

At 53°28′0″N 2°14′0″W, 160 miles (260 km) northwest of London, Manchester lies in a bowl-shaped land area bordered to the north and east by the Pennines, an upland chain that runs the length of northern England, and to the south by the Cheshire Plain. Manchester is 35.0 miles (56.3 km) north-east of Liverpool and 35.0 miles (56.3 km) north-west of Sheffield, making the city the halfway point between the two. The city centre is on the east bank of the River Irwell, near its confluences with the Rivers Medlock and Irk, and is relatively low-lying, being between 35 and 42 metres (115 and 138 feet) above sea level.[68] The River Mersey flows through the south of Manchester. Much of the inner city, especially in the south, is flat, offering extensive views from many highrise buildings in the city of the foothills and moors of the Pennines, which can often be capped with snow in the winter months. Manchester’s geographic features were highly influential in its early development as the world’s first industrial city. These features are its climate, its proximity to a seaport at Liverpool, the availability of waterpower from its rivers, and its nearby coal reserves.[69]

The name Manchester, though officially applied only to the metropolitan district within Greater Manchester, has been applied to other, wider divisions of land, particularly across much of the Greater Manchester county and urban area. The “Manchester City Zone”, “Manchester post town” and the “Manchester Congestion Charge” are all examples of this.

For purposes of the Office for National Statistics, Manchester forms the most populous settlement within the Greater Manchester Urban Area, the United Kingdom’s second-largest conurbation. There is a mix of high-density urban and suburban locations. The largest open space in the city, at around 260 hectares (642 acres),[70] is Heaton Park. Manchester is contiguous on all sides with several large settlements, except for a small section along its southern boundary with Cheshire. The M60 and M56 motorways pass through Northenden and Wythenshawe respectively in the south of Manchester. Heavy rail lines enter the city from all directions, the principal destination being Manchester Piccadilly station.

Climate

Manchester experiences a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), like much of the British Isles, with warm summers and cold winters compared to other parts of the UK. Summer daytime temperatures regularly top 20 °C, quite often reaching 25 °C on sunny days during July and August in particular. In more recent years, temperatures have occasionally reached over 30 °C. There is regular but generally light precipitation throughout the year. The city’s average annual rainfall is 806.6 millimetres (31.76 in)[71] compared to a UK average of 1,125.0 millimetres (44.29 in),[72] and its mean rain days are 140.4 per annum,[71] compared to the UK average of 154.4.[72] Manchester has a relatively high humidity level, and this, along with abundant soft water, was one factor that led to advancement of the textile industry in the area.[73] Snowfalls are not common in the city because of the urban warming effect but the West Pennine Moors to the north-west, South Pennines to the north-east and Peak District to the east receive more snow, which can close roads leading out of the city.[74] They include the A62 via Oldham and Standedge,[75] the A57, Snake Pass, towards Sheffield,[76] and the Pennine section of the M62.[77] The lowest temperature ever recorded in Manchester was −17.6 °C (0.3 °F) on 7 January 2010.[78] The highest temperature recorded in Manchester is 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) on 19 July 2022, during the 2022 European Heatwave.[79]

Green belt

Further information: North West Green Belt

Manchester lies at the centre of a green belt region extending into the wider surrounding counties. This reduces urban sprawl, prevents towns in the conurbation from further convergence, protects the identity of outlying communities, and preserves nearby countryside. It is achieved by restricting inappropriate development within the designated areas and imposing stricter conditions on permitted building.[88]

Due to being already highly urban, the city contains limited portions of protected green-belt area within greenfield throughout the borough, with minimal development opportunities,[89] at Clayton Vale, Heaton Park, Chorlton Water Park along with the Chorlton Ees & Ivy Green nature reserve and the floodplain surrounding the River Mersey, as well as the southern area around Manchester Airport.[90] The green belt was first drawn up in 1961.[88]

Demographics

Main article: Demographics of Manchester

Historically the population of Manchester began to increase rapidly during the Victorian era, estimated at 354,930 for Manchester and 110,833 for Salford in 1865,[91] and peaking at 766,311 in 1931. From then the population began to decrease rapidly, due to slum clearance and the increased building of social housing overspill estates by Manchester City Council after the Second World War such as Hattersley and Langley.[92]

The 2012 mid-year estimate for the population of Manchester was 510,700. This was an increase of 7,900, or 1.6 per cent, since the 2011 estimate. Since 2001, the population has grown by 87,900, or 20.8 per cent, making Manchester the third fastest-growing area in the 2011 census.[93] The city experienced the greatest percentage population growth outside London, with an increase of 19 per cent to over 500,000.[94] Manchester’s population is projected to reach 532,200 by 2021, an increase of 5.8 per cent from 2011. This represents a slower rate of growth than the previous decade.[93]

The Greater Manchester Built-up Area in 2011 had an estimated population of 2,553,400. In 2012 an estimated 2,702,200 people lived in Greater Manchester. An 6,547,000 people were estimated in 2012 to live within 30 miles (50 km) of Manchester and 11,694,000 within 50 miles (80 km).[93]

Between the beginning of July 2011 and end of June 2012 (mid-year estimate date), births exceeded deaths by 4,800. Migration (internal and international) and other changes accounted for a net increase of 3,100 people between July 2011 and June 2012. Compared with Greater Manchester and with England, Manchester has a younger population, with a particularly large 20–35 age group.[93]

There were 76,095 undergraduate and postgraduate students at Manchester Metropolitan University, the University of Manchester and Royal Northern College of Music in the 2011/2012 academic year.

Of all households in Manchester, 0.23 per cent were Same-Sex Civil Partnership households, compared with an English national average of 0.16 per cent in 2011.[95]

The Manchester Larger Urban Zone, a Eurostat measure of the functional city-region approximated to local government districts, had a population of 2,539,100 in 2004.[96] In addition to Manchester itself, the LUZ includes the remainder of the county of Greater Manchester.[97] The Manchester LUZ is the second largest within the United Kingdom, behind that of London.

Religion

Religious beliefs, according to the 2021 census[98]

- Christian (36.2%)

- No Religion (32.4%)

- Muslim (22.3%)

- Hindu (1.1%)

- Buddhist (0.6%)

- Jewish (0.5%)

- Other (0.5%)

- Religion Not Stated (5.9%)

Since the 2001 census, the proportion of Christians in Manchester has fallen by 22 per cent from 62.4 per cent to 48.7 per cent in 2011. The proportion of those with no religious affiliation rose by 58.1 per cent from 16 per cent to 25.3 per cent, whilst the proportion of Muslims increased by 73.6 per cent from 9.1 per cent to 15.8 per cent. The size of the Jewish population in Greater Manchester is the largest in Britain outside London.[99]

Ethnicity

In terms of ethnic composition, the City of Manchester has the highest non-white proportion of any district in Greater Manchester. Statistics from the 2011 census showed that 66.7 per cent of the population was White (59.3 per cent White British, 2.4 per cent White Irish, 0.1 per cent Gypsy or Irish Traveller, 4.9 per cent Other White – although the size of mixed European and British ethnic groups is unclear, there are reportedly over 25,000 people in Greater Manchester of at least partial Italian descent alone, which represents 5.5 per cent of the population of Greater Manchester[100]). 4.7 per cent were mixed race (1.8 per cent White and Black Caribbean, 0.9 per cent White and Black African, 1.0 per cent White and Asian, 1.0 per cent other mixed), 17.1 per cent Asian (2.3 per cent Indian, 8.5 per cent Pakistani, 1.3 per cent Bangladeshi, 2.7 per cent Chinese, 2.3 per cent other Asian), 8.6 per cent Black (5.1 per cent African, 1.6 per cent other Black), 1.9 per cent Arab and 1.2 per cent of other ethnic heritage.[101]

Kidd identifies Moss Side, Longsight, Cheetham Hill, Rusholme, as centres of population for ethnic minorities.[23] Manchester’s Irish Festival, including a St Patrick’s Day parade, is one of Europe’s largest.[102] There is also a well-established Chinatown in the city with a substantial number of Chinese restaurants and supermarkets. The area also attracts large numbers of Chinese students to the city who, in attending the local universities,[103] contribute to Manchester having the third-largest Chinese population in Europe.[104][105]

Ethnicity of Manchester, from 1971 to 2021:

| Ethnic group | showYear | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ethnicity of school pupils

Economy

Main article: Economy of Manchester

See also: List of companies based in Greater Manchester

| Year | GVA (£ million) | Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 24,011 | |

| 2003 | 25,063 | |

| 2004 | 27,862 | |

| 2005 | 28,579 | |

| 2006 | 30,384 | |

| 2007 | 32,011 | |

| 2008 | 32,081 | |

| 2009 | 33,186 | |

| 2010 | 33,751 | |

| 2011 | 33,468 | |

| 2012 | 34,755 | |

| 2013 | 37,560 |

The Office for National Statistics does not produce economic data for the City of Manchester alone, but includes four other metropolitan boroughs, Salford, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford, in an area named Greater Manchester South, which had a GVA of £34.8 billion. The economy grew relatively strongly between 2002 and 2012, when growth was 2.3 per cent above the national average.[115] The wider metropolitan economy is the third largest in the United Kingdom. It is ranked as a beta world city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[116]

As the UK economy continues to recover from its 2008–2010 downturn, Manchester compares favourably according to recent figures. In 2012 it showed the strongest annual growth in business stock (5 per cent) of all core cities.[117] The city had a relatively sharp increase in the number of business deaths, the largest increase in all the core cities, but this was offset by strong growth in new businesses, resulting in strong net growth.

Manchester’s civic leadership has a reputation for business acumen.[118] It owns two of the country’s four busiest airports and uses its earnings to fund local projects.[119] Meanwhile, KPMG‘s competitive alternative report found that in 2012 Manchester had the 9th lowest tax cost of any industrialised city in the world,[120] and fiscal devolution has come earlier to Manchester than to any other British city: it can keep half the extra taxes it gets from transport investment.[118]

KPMG’s competitive alternative report also found that Manchester was Europe’s most affordable city featured, ranking slightly better than the Dutch cities of Rotterdam and Amsterdam, which all have a cost-of-living index of less than 95.[120]

Manchester is a city of contrast, where some of the country’s most deprived and most affluent neighbourhoods can be found.[121][122] According to 2010 Indices of Multiple Deprivation, Manchester is the 4th most deprived local council in England.[123] Unemployment throughout 2012–2013 averaged 11.9 per cent, which was above national average, but lower than some of the country’s comparable large cities.[124] On the other hand, Greater Manchester is home to more multi-millionaires than anywhere outside London, with the City of Manchester taking up most of the tally.[125] In 2013 Manchester was ranked 6th in the UK for quality of life, according to a rating of the UK’s 12 largest cities.[126]

Women fare better in Manchester than the rest of the country in comparative pay with men. The per hours-worked gender pay gap is 3.3 per cent compared with 11.1 per cent for Britain.[127] 37 per cent of the working-age population in Manchester have degree-level qualifications, as opposed to an average of 33 per cent across other core cities,[127] although its schools under-perform slightly compared with the national average.[128]

Manchester has the largest UK office market outside London, according to GVA Grimley, with a quarterly office uptake (averaged over 2010–2014) of some 250,000 square feet – equivalent to the quarterly office uptake of Leeds, Liverpool and Newcastle combined and 90,000 square feet more than the nearest rival, Birmingham.[129] The strong office market in Manchester has been partly attributed to “northshoring” (from offshoring), which entails the relocation or alternative creation of jobs away from the overheated South to areas where office space is possibly cheaper and the workforce market less saturated.[130]

A view of the Manchester skyline, January 2020

Landmarks

Main article: Architecture of Manchester

See also: List of tallest buildings and structures in Manchester, List of streets and roads in Manchester, Grade I listed buildings in Greater Manchester, Grade II* listed buildings in Greater Manchester, and List of public art in Greater Manchester

Manchester’s buildings display a variety of architectural styles, ranging from Victorian to contemporary architecture. The widespread use of red brick characterises the city, much of the architecture of which harks back to its days as a global centre for the cotton trade.[28] Just outside the immediate city centre are a large number of former cotton mills, some of which have been left virtually untouched since their closure, while many have been redeveloped as apartment buildings and office space. Manchester Town Hall, in Albert Square, was built in the Gothic revival style.[131]

Manchester also has a number of skyscrapers built in the 1960s and 1970s, the tallest being the CIS Tower near Manchester Victoria station until the Beetham Tower was completed in 2006. The latter exemplifies a new surge in high-rise building. It includes a Hilton hotel, a restaurant and apartments. The largest skyscraper is now Deansgate Square South Tower, at 201 metres (659 feet).The Green Building, opposite Oxford Road station, is a eco-friendly housing project, while the recently completed One Angel Square, is one of the most sustainable large buildings in the world.[132]

Heaton Park in the north of the city borough is one of the largest municipal parks in Europe, covering 610 acres (250 ha) of parkland.[133] The city has 135 parks, gardens, and open spaces.[134]

Two large squares hold many of Manchester’s public monuments. Albert Square has monuments to Prince Albert, Bishop James Fraser, Oliver Heywood, William Gladstone and John Bright. Piccadilly Gardens has monuments dedicated to Queen Victoria, Robert Peel, James Watt and the Duke of Wellington. The cenotaph in St Peter’s Square is Manchester’s main memorial to its war dead. Designed by Edwin Lutyens, it echoes the original on Whitehall in London. The Alan Turing Memorial in Sackville Park commemorates his role as the father of modern computing. A larger-than-life statue of Abraham Lincoln by George Gray Barnard in the eponymous Lincoln Square (having stood for many years in Platt Fields) was presented to the city by Mr and Mrs Charles Phelps Taft of Cincinnati, Ohio, to mark the part Lancashire played in the cotton famine and American Civil War of 1861–1865.[135] A Concorde is on display near Manchester Airport.

Manchester has six designated local nature reserves: Chorlton Water Park, Blackley Forest, Clayton Vale and Chorlton Ees, Ivy Green, Boggart Hole Clough and Highfield Country Park.[136]

Transport

Main article: Transport in Manchester

See also: Transport for Greater Manchester

Rail

Manchester Liverpool Road was the world’s first purpose-built passenger and goods railway station[137] and served as the Manchester terminus on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway – the world’s first inter-city passenger railway. It is still extant and its buildings form part of the Science & Industry Museum.

Two of the city’s four main line termini did not survive the 1960s: Manchester Central and Manchester Exchange each closed in 1969. In addition, Manchester Mayfield station closed to passenger services in 1960; its buildings and platforms are still extant, next to Piccadilly station, but are due to be redeveloped in the 2020s.

Today, the city is well served by its rail network although it is now working to capacity,[139] and is at the centre of an extensive county-wide railway network, including the West Coast Main Line, with two mainline stations: Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria. The Manchester station group – comprising Manchester Piccadilly, Manchester Victoria, Manchester Oxford Road and Deansgate – is the third busiest in the United Kingdom, with 44.9 million passengers recorded in 2017/2018.[138] The High Speed 2 link to Birmingham and London was also planned, which would have included a 12 km (7 mi) tunnel under Manchester on the final approach into an upgraded Piccadilly station,[140] however this was cancelled by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in October 2023.[141]

Recent improvements in Manchester as part of the Northern Hub in the 2010s have been numerous electrification schemes into and through Manchester, redevelopment of Victoria station and construction of the Ordsall Chord directly linking Victoria and Piccadilly.[142] Work on two new through platforms at Piccadilly and an extensive upgrade at Oxford Road had not commenced as of 2019. Manchester city centre, specifically the Castlefield Corridor, suffers from constrained rail capacity that frequently leads to delays and cancellations – a 2018 report found that all three major Manchester stations are among the top ten worst stations in the United Kingdom for punctuality, with Oxford Road deemed the worst in the country.[143]

Metrolink (tram/light rail)

Main article: Manchester Metrolink

Manchester became the first city in the UK to acquire a modern light rail tram system when the Manchester Metrolink opened in 1992. In 2016–2017, 37.8 million passenger journeys were made on the system.[145] The present system mostly runs on former commuter rail lines converted for light rail use, and crosses the city centre via on-street tram lines.[146] The network consists of eight lines with 99 stops.[147] A new line to the Trafford Centre opened in 2020.[148][149] Manchester city centre is also serviced by over a dozen heavy and light rail-based park and ride sites.[150]

Bus

The city has one of the most extensive bus networks outside London, with over 50 bus companies operating in the Greater Manchester region radiating from the city. In 2011, 80 per cent of public transport journeys in Greater Manchester were made by bus, amounting to 220 million passenger journeys each year.[151] After deregulation in 1986, the bus system was taken over by GM Buses, which after privatisation was split into GM Buses North and GM Buses South. Later these were taken over by First Greater Manchester and Stagecoach Manchester. Much of the First Greater Manchester business was sold to Diamond North West and Go North West in 2019.[152] Go North West operate a three-route zero-fare Manchester Metroshuttle, which carries 2.8 million commuters a year around Manchester’s business districts.[151][153][154] Stagecoach Manchester is the Stagecoach Group‘s largest subsidiary and operates around 690 buses.[155]

Air

Main article: Manchester Airport

Manchester Airport serves Manchester, Northern England and North Wales. The airport is the third busiest in the United Kingdom, with over double the number of annual passengers of the next busiest non-London airport.[156] Services cover many destinations in Europe, North America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia (with more destinations from Manchester than any other airport in Britain).[157] A second runway was opened in 2001 and there have been continued terminal improvements. The airport has the highest rating available: “Category 10“, encompassing an elite group of airports able to handle “Code F” aircraft, including the Airbus A380 and Boeing 747-8.[158] From September 2010 the airport became one of only 17 airports in the world and the only UK airport other than Heathrow Airport and Gatwick Airport to operate the Airbus A380.[159]

A smaller City Airport Manchester exists 9.3 km (6 mi) to the west of Manchester city centre. It was Manchester’s first municipal airport and became the site of the first air traffic control tower in the UK, and the first municipal airfield in the UK to be licensed by the Air Ministry.[160] Today, private charter flights and general aviation use City. It also has a flight school,[161] and both the Greater Manchester Police Air Support Unit and the North West Air Ambulance have helicopters based there.

Canal

An extensive canal network, including the Manchester Ship Canal, was built to carry freight from the Industrial Revolution onward; the canals are still maintained, though now largely repurposed for leisure use.[162] In 2012, plans were approved to introduce a water taxi service between Manchester city centre and MediaCityUK at Salford Quays.[163] It ceased to operate in June 2018, citing poor infrastructure.[164]

Cycling

Further information: Cycling in Greater Manchester

Cycling for transportation and leisure enjoys popularity in Manchester and the city also plays a major role in British cycle racing.[165][166]

Culture

Main article: Culture of Manchester

See also: List of people from Manchester

Music

See also: Popular music of Manchester, List of music artists and bands from Manchester, and Madchester

Bands that have emerged from the Manchester music scene include Van der Graaf Generator, Oasis, the Smiths, Joy Division and its successor group New Order, Buzzcocks, the Stone Roses, the Fall, the Durutti Column, 10cc, Godley & Creme, the Verve, Elbow, Doves, the Charlatans, M People, the 1975, Simply Red, Take That, Dutch Uncles, Everything Everything, the Courteeners, Pale Waves, and the Outfield. Manchester was credited as the main driving force behind British indie music of the 1980s led by the Smiths, later including the Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets, and James. The later groups came from what became known as the “Madchester” scene that also centred on The Haçienda nightclub developed by the founder of Factory Records, Tony Wilson. Although from southern England, the Chemical Brothers subsequently formed in Manchester.[167] Former Smiths frontman Morrissey, whose lyrics often refer to Manchester locations and culture, later found international success as a solo artist. Previously, notable Manchester acts of the 1960s include the Hollies, Herman’s Hermits, and Davy Jones of the Monkees (famed in the mid-1960s for their albums and their American TV show), and the earlier Bee Gees, who grew up in Chorlton.[168] Prominent rap artists from Manchester include Bugzy Malone and Aitch.

Its main pop music venue is Manchester Arena, voted “International Venue of the Year” in 2007.[169] With over 21,000 seats, it is the largest arena of its type in Europe.[169] In terms of concertgoers, it is the busiest indoor arena in the world, ahead of Madison Square Garden in New York and The O2 Arena in London, which are second and third busiest.[170] Other venues include Manchester Apollo, Albert Hall, Victoria Warehouse and the Manchester Academy. Smaller venues include the Band on the Wall, the Night and Day Café,[171] the Ruby Lounge,[172] and The Deaf Institute.[173] Manchester also has the most indie and rock music events outside London.[174]

Manchester has two symphony orchestras, The Hallé and the BBC Philharmonic, and a chamber orchestra, the Manchester Camerata. In the 1950s, the city was home to a so-called “Manchester School” of classical composers, which was composed of Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Maxwell Davies, David Ellis and Alexander Goehr. Manchester is a centre for musical education: the Royal Northern College of Music and Chetham’s School of Music.[175] Forerunners of the RNCM were the Northern School of Music (founded 1920) and the Royal Manchester College of Music (founded 1893), which merged in 1973. One of the earliest instructors and classical music pianists/conductors at the RNCM, shortly after its founding, was the Russian-born Arthur Friedheim, (1859–1932), who later had the music library at the famed Peabody Institute conservatory of music in Baltimore, Maryland, named after him. The main classical music venue was the Free Trade Hall on Peter Street until the opening in 1996 of the 2,500 seat Bridgewater Hall.[176]

Brass band music, a tradition in the north of England, is important to Manchester’s musical heritage;[177] some of the UK’s leading bands, such as the CWS Manchester Band and the Fairey Band, are from Manchester and surrounding areas, and the Whit Friday brass-band contest takes place annually in the neighbouring areas of Saddleworth and Tameside.

Performing arts

Manchester has a thriving theatre, opera and dance scene, with a number of large performance venues, including Manchester Opera House, which feature large-scale touring shows and West End productions; the Palace Theatre; and the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester’s former cotton exchange, which is the largest theatre in the round in the UK.

Smaller venues include the Contact Theatre and Z-arts in Hulme. The Dancehouse on Oxford Road is dedicated to dance productions.[178] In 2014, HOME, a new custom-built arts complex opened. Housing two theatre spaces, five cinemas and an art exhibition space, it replaced the Cornerhouse and The Library Theatre.[179]

Since 2007, the city has hosted the Manchester International Festival, a biennial international arts festival with a focus on original work, which has included major new commissions by artists, including Bjork. In 2023, the festival, operated by Factory International, was given a permanent home in Aviva Studios, a purpose-built multi-million pound venue designed by Rem Koolhaas from the Office for Metropolitan Architecture.[180]

Museums and galleries

Manchester’s museums celebrate Manchester’s Roman history, rich industrial heritage and its role in the Industrial Revolution, the textile industry, the Trade Union movement, women’s suffrage and football. A reconstructed part of the Roman fort of Mamucium is open to the public in Castlefield.

The Science and Industry Museum, housed in the former Liverpool Road railway station, has a large collection of steam locomotives, industrial machinery, aircraft and a replica of the world’s first stored computer program (known as the Manchester Baby).[181] The Museum of Transport displays a collection of historic buses and trams.[182] Trafford Park in the neighbouring borough of Trafford is home to Imperial War Museum North.[183] The Manchester Museum opened to the public in the 1880s, has notable Egyptology and natural history collections.[184] Other exhibition spaces and museums in Manchester include Islington Mill in Salford, the National Football Museum at Urbis, Castlefield Gallery, the Manchester Costume Gallery at Platt Fields Park, the People’s History Museum and the Manchester Jewish Museum.[185]

The municipally owned Manchester Art Gallery in Mosley Street houses a permanent collection of European painting and one of Britain’s main collections of Pre-Raphaelite paintings.[186][187] In the south of the city, the Whitworth Art Gallery displays modern art, sculpture and textiles and was voted Museum of the Year in 2015.[188] The work of Stretford-born painter L. S. Lowry, known for “matchstick” paintings of industrial Manchester and Salford, can be seen in the City and Whitworth Manchester galleries, and at the Lowry art centre in Salford Quays (in the neighbouring borough of Salford), which devotes a large permanent exhibition to his works.[189]

Literature

Manchester is a UNESCO City of Literature known for a “radical literary history”.[190][191] Manchester in the 19th century featured in works highlighting the changes that industrialisation had brought. They include Elizabeth Gaskell‘s novel Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life (1848),[192] and studies such as The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 by Friedrich Engels, while living and working here.[193] Manchester was the meeting place of Engels and Karl Marx. The two began writing The Communist Manifesto in Chetham’s Library[194] – founded in 1653 and claiming to be the oldest public library in the English-speaking world. Elsewhere in the city, the John Rylands Library holds an extensive collection of early printing. The Rylands Library Papyrus P52, believed to be the earliest extant New Testament text, is on permanent display there.[195]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

‘Manchester’ a poetical illustration by L. E. L.

Letitia Landon‘s poetical illustration Manchester to a vista over the city by G. Pickering in Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1835, records the rapid growth of the city and its cultural importance.[196]

Charles Dickens is reputed to have set his novel Hard Times in the city, and though partly modelled on Preston, it shows the influence of his friend Mrs Gaskell.[197] Gaskell penned all her novels but Mary Barton at her home in 84 Plymouth Grove. Often her house played host to influential authors: Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Charles Eliot Norton, for example.[198] It is now open as a literary museum.

Charlotte Brontë began writing her novel Jane Eyre in 1846, while staying at lodgings in Hulme. She was accompanying her father Patrick, who was convalescing in the city after cataract surgery.[199] She probably envisioned Manchester Cathedral churchyard as the burial place for Jane’s parents and the birthplace of Jane herself.[200] Also associated with the city is the Victorian poet and novelist Isabella Banks, famed for her 1876 novel The Manchester Man. Anglo-American author Frances Hodgson Burnett was born in the city’s Cheetham Hill district in 1849, and wrote much of her classic children’s novel The Secret Garden while visiting nearby Salford’s Buile Hill Park.[201]

Anthony Burgess is among the 20th-century writers who made Manchester their home. He wrote here the dystopian satire A Clockwork Orange in 1962.[202] Dame Carol Ann Duffy, Poet Laureate from 2009 to 2019, moved to the city in 1996 and lives in West Didsbury.[203]

Nightlife

The night-time economy of Manchester has expanded significantly since about 1993, with investment from breweries in bars, public houses and clubs, along with active support from the local authorities.[204] The more than 500 licensed premises[205] in the city centre have a capacity to deal with more than 250,000 visitors,[206] with 110,000–130,000 people visiting on a typical weekend night,[205] making Manchester the most popular city for events at 79 per thousand people.[207] The night-time economy has a value of about £100 million,[208] and supports 12,000 jobs.[205]

The Madchester scene of the 1980s, from which groups including the Stone Roses, the Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets, 808 State, James and the Charlatans emerged, was based around clubs such as The Haçienda.[209] The period was the subject of the movie 24 Hour Party People. Many of the big clubs suffered problems with organised crime at that time; Haslam describes one where staff were so completely intimidated that free admission and drinks were demanded (and given) and drugs were openly dealt.[209] Following a series of drug-related violent incidents, The Haçienda closed in 1997.[204]

Gay village

Public houses in the Canal Street area have had an LGBTQ+ clientele since at least 1940,[204] and now form the centre of Manchester’s LGBTQ+ community. Since the opening of new bars and clubs, the area attracts 20,000 visitors each weekend[204] and has hosted a popular festival, Manchester Pride, each August since 1995.[210]

Education

See also: List of schools in Manchester

There are three universities in the City of Manchester. The University of Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University and Royal Northern College of Music. The University of Manchester is the second largest full-time non-collegiate university in the United Kingdom,[211] created in 2004 by the merger of Victoria University of Manchester, founded in 1904, and UMIST, founded in 1956,[212] having developed from the Mechanics’ Institute founded, as indicated in the university’s logo, in 1824. The University of Manchester includes the Manchester Business School, which offered the first MBA course in the UK in 1965.[213]

Manchester Metropolitan University was formed as Manchester Polytechnic on the merger of three colleges in 1970. It gained university status in 1992, and in the same year absorbed Crewe and Alsager College of Higher Education in South Cheshire.[214] The Cheshire campus permanently closed in 2019.[215] The University of Law, the largest provider of vocation legal training in Europe, has a campus in the city.[216]

The three universities are grouped around Oxford Road on the southern side of the city centre, which forms Europe’s largest urban higher-education precinct.[217] Together they have a combined population of over 80,000 students as of 2022.[211]

One of Manchester’s notable secondary schools is Manchester Grammar School. Established in 1515,[218] as a free grammar school next to what is now the cathedral, it moved in 1931 to Old Hall Lane in Fallowfield, south Manchester, to accommodate the growing student body. In the post-war period, it was a direct grant grammar school (i.e. partially state funded), but it reverted to independent status in 1976 after abolition of the direct-grant system.[219] Its previous premises are now used by Chetham’s School of Music. There are three schools nearby: William Hulme’s Grammar School, Withington Girls’ School and Manchester High School for Girls.

In 2019, the Manchester Local Education Authority was ranked second to last out of Greater Manchester’s ten LEAs and 140th out of 151 in the country LEAs based on the percentage of pupils attaining grades 4 or above in English and mathematics GCSEs (General Certificate of Secondary Education) with 56.2 per cent compared with the national average of 64.9 per cent.[220] Of the 63 secondary schools in the LEA, four had 80 per cent or more pupils achieving Grade 4 or above in English and maths GCSEs: Manchester High School for Girls, The King David High School, Manchester Islamic High School for Girls, and Kassim Darwish Grammar School for Boys.[221]

Sport

Main article: Sport in Manchester

Two Premier League football clubs bear the city’s name – Manchester City and Manchester United.[222] Manchester City’s home is the City of Manchester Stadium in east Manchester, built for the 2002 Commonwealth Games and then reconfigured as a football ground in 2003. Manchester United, despite originating in Manchester, have been based in the neighbouring borough of Trafford since 1910. Their stadium Old Trafford is adjacent to Lancashire County Cricket Club ground, also called Old Trafford. The cricket club has strong association with Manchester due to proximity to the city and Manchester historically being part of Lancashire.[223]

Sporting facilities built for the 2002 Commonwealth Games include the City of Manchester Stadium, National Squash Centre and Manchester Aquatics Centre.[224] Manchester has competed twice to host the Olympic Games, beaten by Atlanta for 1996 and Sydney for 2000. The National Cycling Centre includes a velodrome, BMX Arena and Mountainbike trials, and is the home of British Cycling, UCI ProTeam Team Sky and Sky Track Cycling. The Manchester Velodrome, built as a part of the bid for the 2000 games, has become a catalyst for British success in cycling.[204] The velodrome hosted the UCI Track Cycling World Championships for a record third time in 2008. The National Indoor BMX Arena (2,000 capacity) adjacent to the velodrome opened in 2011. The Manchester Arena hosted the FINA World Swimming Championships in 2008.[225] Manchester hosted the World Squash Championships in 2008,[226] the 2010 World Lacrosse Championship,[227] the 2013 Ashes series, 2013 Rugby League World Cup, 2015 Rugby World Cup and 2019 Cricket World Cup.

Media

Main article: Media in Manchester

See also: List of television programmes set, produced or filmed in Manchester; Films set in Manchester; and List of national radio programmes made in Manchester

The Guardian newspaper was founded in the city in 1821 as The Manchester Guardian. Until 2008, its head office was still in the city, though many of its management functions were moved to London in 1964.[23][228] For many years most national newspapers had offices in Manchester: The Daily Telegraph, Daily Express, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, The Sun. At its height, 1,500 journalists were employed, earning the city the nickname “second Fleet Street“. In the 1980s the titles closed their northern offices and centred their operations in London.[229]

The main regional newspaper in the city is the Manchester Evening News, which was for over 80 years the sister publication of The Manchester Guardian.[228] The Manchester Evening News has the largest circulation of a UK regional evening newspaper and is distributed free of charge in the city centre on Thursdays and Fridays, but paid for in the suburbs. Despite its title, it is available all day.[230]

Several local weekly free papers are distributed by the MEN group. The Metro North West is available free at Metrolink stops, rail stations and other busy locations. [231]

An attempt to launch a Northern daily newspaper, the North West Times, employing journalists made redundant by other titles, closed in 1988.[232] Another attempt was made with the North West Enquirer, which hoped to provide a true “regional” newspaper for the North West, much in the same vein as the Yorkshire Post does for Yorkshire or The Northern Echo does for the North East; it folded in October 2006.[232]

Television

Manchester has been a centre of television broadcasting since the 1950s. A number of television studios have been in operation around the city, and have since relocated to MediaCityUK in neighbouring Salford.

The ITV franchise Granada Television has been based in Manchester since 1954. Now based at MediaCityUK, the company’s former headquarters at Granada Studios on Quay Street with its distinctive illuminated sign were a prominent landmark on the Manchester skyline for several decades.[233][234][235] Granada produces Coronation Street,[236] local news and programmes for North West England. Although its influence has waned, Granada had been described as “the best commercial television company in the world”.[237][238]

With the growth in regional television in the 1950s, Manchester became one of the BBC‘s three main centres in England.[234] In 1954, the BBC opened its first regional BBC Television studio outside London, Dickenson Road Studios, in a converted Methodist chapel in Rusholme. The first edition of Top of the Pops was broadcast here on New Year’s Day 1964.[239][240] From 1975, BBC programmes including Mastermind,[241] and Real Story,[242] were made at New Broadcasting House on Oxford Road. The Cutting It series set in the city’s Northern Quarter and The Street were set in Manchester[243] as was Life on Mars. Manchester was the regional base for BBC One North West Region programmes before it relocated to MediaCityUK in nearby Salford Quays.[244][245]

The Manchester television channel, Channel M, owned by the Guardian Media Group operated from 2000, but closed in 2012.[234][246] Manchester is also covered by two internet television channels: Quays News and Manchester.tv. The city had a new terrestrial channel from January 2014 when YourTV Manchester, which won the OFCOM licence bid in February 2013. It began its first broadcast, but in 2015, That’s Manchester took over to air on 31 May and launched the freeview channel 8 service slot, before moving to channel 7 in April 2016.

Radio

The city has the highest number of local radio stations outside London, including BBC Radio Manchester, Hits Radio Manchester, Capital Manchester and Lancashire, Greatest Hits Radio Manchester & The North West, Heart North West, Smooth North West, Gold, Radio X and NMFM (North Manchester FM).[247] Student radio stations include Fuse FM at the University of Manchester and MMU Radio at the Manchester Metropolitan University.[248] A community radio network is coordinated by Radio Regen, with stations covering Ardwick, Longsight and Levenshulme (All FM 96.9) and Wythenshawe (Wythenshawe FM 97.2).[247] Defunct radio stations include Sunset 102, which became Kiss 102, then Galaxy Manchester, and KFM which became Signal Cheshire (later Imagine FM). These stations and pirate radio played a significant role in the city’s house music culture, the Madchester scene.

Twin cities

Manchester has formal twinning arrangements (or “friendship agreements”) with several places.[249][250] In addition, the British Council maintains a metropolitan centre in Manchester.[251]

- Amsterdam, Netherlands[252] (2007)

- Bilwi, Nicaragua[252]

- Chemnitz, Germany (1983)[253]

- Córdoba, Spain[252]

- Faisalabad, Pakistan (1997)[252]

- Los Angeles, United States (2009)

- Rehovot, Israel[252]

- Saint Petersburg, Russia[252] (1962)

- Wuhan, China (1986)[254]

- Osaka, Japan[252]

Manchester is home to the largest group of consuls in the UK outside London. The expansion of international trade links during the Industrial Revolution led to the introduction of the first consuls in the 1820s and since then over 800, from all parts of the world, have been based in Manchester. Manchester hosts consular services for most of the north of England.